Studying the relationship between fonts and reading performance, including the case of Learning Disabilities, we have identified the need for a font that would allow to check some of the typographical features relevant to the reading process.

Luciano Perondi therefore has reworked Titilium, and released a font with Open Font license. We called the result TestMe.

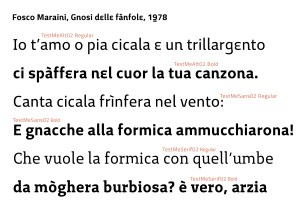

The font TestMe is available in 4 versions based on the same parameters except serifs and differentiation of forms: – TestMe Sans (sans-serif), wide spacing, long ascenders and descenders; – TestMe Sans Alternate, with serifs only on a few letters and forms more clearly differentiated; – TestMe Serif, with serifs on all the letters (still incomplete, missing diacritics and marks); (- TestMe Serif Alternate, forthcoming).

You can download TestMe for free at this link (Open Font License is included): https://github.com/molotro/TestMe02 You can use and modify the font according to the license.

We decided to release it as a “Libre” font because we think that it’s useless to give a single solution to a specific problem. If you have any suggestion or specific needs, please write us, we’ll be glad to have advices to expand the font or your personal customizations.

The practice of Design for All “requires the involvement of end users at every stage in the design process”. For this reason the font is released as a draft, it will be updated little by little with your help, use it with care.

Luciano Perondi & Leonardo Romei

////////////////////////////

In seguito allo studio del rapporto tra font e efficacia delle performance di lettura, compreso il caso dei DSA (disturbi specifici dell’apprendimento), abbiamo individuato la necessità di una font che permettesse di verificare alcune delle caratteristiche tipografiche rilevanti nel processo di lettura.

Luciano Perondi sta dunque rielaborando, a partire da Titilium, una font con licenza Open Font. L’abbiamo chiamata TestMe.

Test Me è presente in 4 versioni uguali rispetto a tutti i parametri tipografici salvo le variazioni relative a grazie e differenziazione delle forme: – TestMe Sans, priva di grazie (sans serif), con spaziatura abbondante e ascendenti e discendenti lughe; – TestMe Sans Alternate, ha le grazie solo su alcune lettere e forme più nettamente differenziate; – TestMe Serif (ancora da completare, mancano gli accenti), ha le grazie su tutte le lettere (serif); (- TestMe Serif Alternate, in arrivo).

TestMe si può scaricare gratuitamente a questo link: https://github.com/molotro/TestMe02

Potete scaricare e modificare il carattere sulla base della licenza allegata. Abbiamo deciso di pubblicare il carattere come carattere libero perché pensiamo che sia inutile darerisposte univoche a un problema specifico.

Se avete suggerimenti o bisogni specifici, siete invitati a scriverci, saremo felici di avere consigli per espandere la font o ricevere le vostre personali modifiche: la pratica del Design for All “esige il coinvolgimento degli utenti finali in ogni fase del processo progettuale“. Per questo motivo le font sono pubblicate allo stadio di prima elaborazione, verranno aggiornate con il vostro aiuto, usatele con cura.

Luciano Perondi & Leonardo Romei

.

.